Source: Will Tooth of MSI

Regional regulation and national policies are putting competing pressures on the scrapping market just as demand is set to rise.

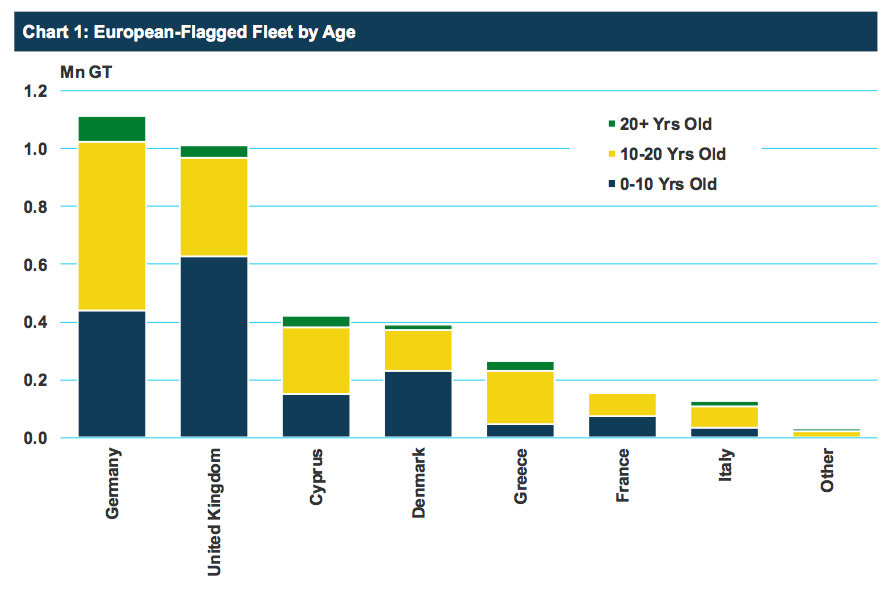

By December 31 2018, all vessels flying the flag of an EU member state (around 12% of the current global merchant fleet) will need to comply with the EU Ship Recycling Regulation (SRR); the rule that brought the Hong Kong Convention into EU law.

From 2019 onwards, any end-of-life, EU-flagged vessel will need to be scrapped at an approved ship recycling facility, a list which the EU last updated in May. Although nothing officially bars any non-EU country from gaining approval, at the moment all 21 shipyards on the list are in the EU and none have experience of breaking large commercial vessels.

The option of flagging vessels out of the EU before selling them as scrap elsewhere is limited as this falls foul of the EU Waste Shipment Regulation legislation that recently caught out Dutch shipowner Seatrade. Seatrade was hit by fines totalling €2.35m after it sold four reefers for scrapping in India, Bangladesh and Turkey; three of the company executives may also face a six-month prison sentence.

As the maritime industry finds itself increasingly faced with legislation designed to tackle the poor condition of current beach scrapping processes, it’s vital for shipbreaking countries to modernise their operations. In Bangladesh, for example, ship scrapping forms an integral part of the economy; Bangladeshi steel production is heavily dependent on the scrap removed from ships and around 50% of the raw materials for steel production come from shipbreaking.

There is still a long way to go before Bangladesh is accepted onto the EU’s list of accepted ship recycling facilities, but a partnership between Maersk and a scrapping facility at Alang in India suggests a way forward.

Modernisation of Asian scrapyards is vital

Maersk has been keen to promote the investment made in improving conditions, safety and environmental impact of the facility, which it now believes is on a par with Chinese and Turkish scrappers. If the facility in Alang is not approved by the EU, Maersk may find itself testing the boundaries of legislation, as much of its fleet sails under a Danish flag.

The option to scrap in China – mostly in dry docks – also seems to be coming to an end with the Chinese government announcing in May that it will no longer be taking foreign ships for scrapping as part of a drive to reduce pollution and waste, resulting in a strengthening of prices as shipbreakers maximise throughput before the end of year cut-off.

The development in China casts the feasibility of the EU’s SRR into doubt. The SRR will come into force prior to the deadline of end 2018 if 2.5 Mn LDT of approved shipbreaking capacity is approved, but at present, just 300,000 LDT has been sanctioned.

Despite the more stringent scrapping policies, we expect the number of vessels scrapped to rise dramatically in 2019. As regulations for ballast water and emissions limits push more vessels out of the market, an increasing number of sub 20-year old vessels will be removed.

To put the situation in context, three quarters of the 200+ ships scrapped in Q1 18 headed to the Indian sub-continent. Accordingly, the solution must be found there. Progress is being made at Indian yards with a number applying to recycle European-flag ships, though concerns remain over subcontractor standards.

A step-change required from the EU

The five Indian yards that are already being considered for EU inclusion would add 323,000 LDT of annual capacity, while four others recently applying would potentially contribute a further 300,000 LDT. The EU must step up its assessment of these yards and ensure that acceptable conditions exist to allow the effective implementation of the Hong Kong Convention.