Global trade corridors are undergoing their most significant realignment in decades as geopolitics, climate constraints and new infrastructure reshape the physical flow of goods. Traditional east–west routes remain dominant, but diversification is accelerating.

1. Established routes remain strong, but their dominance is less absolute

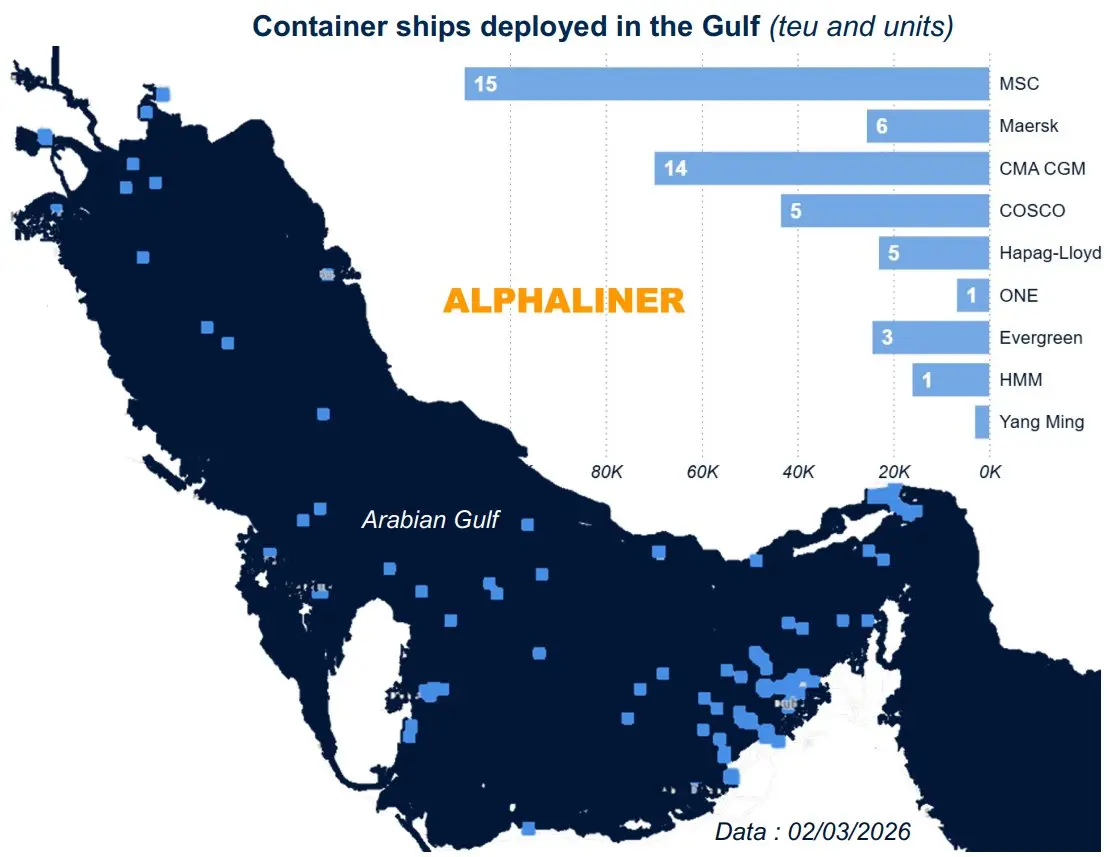

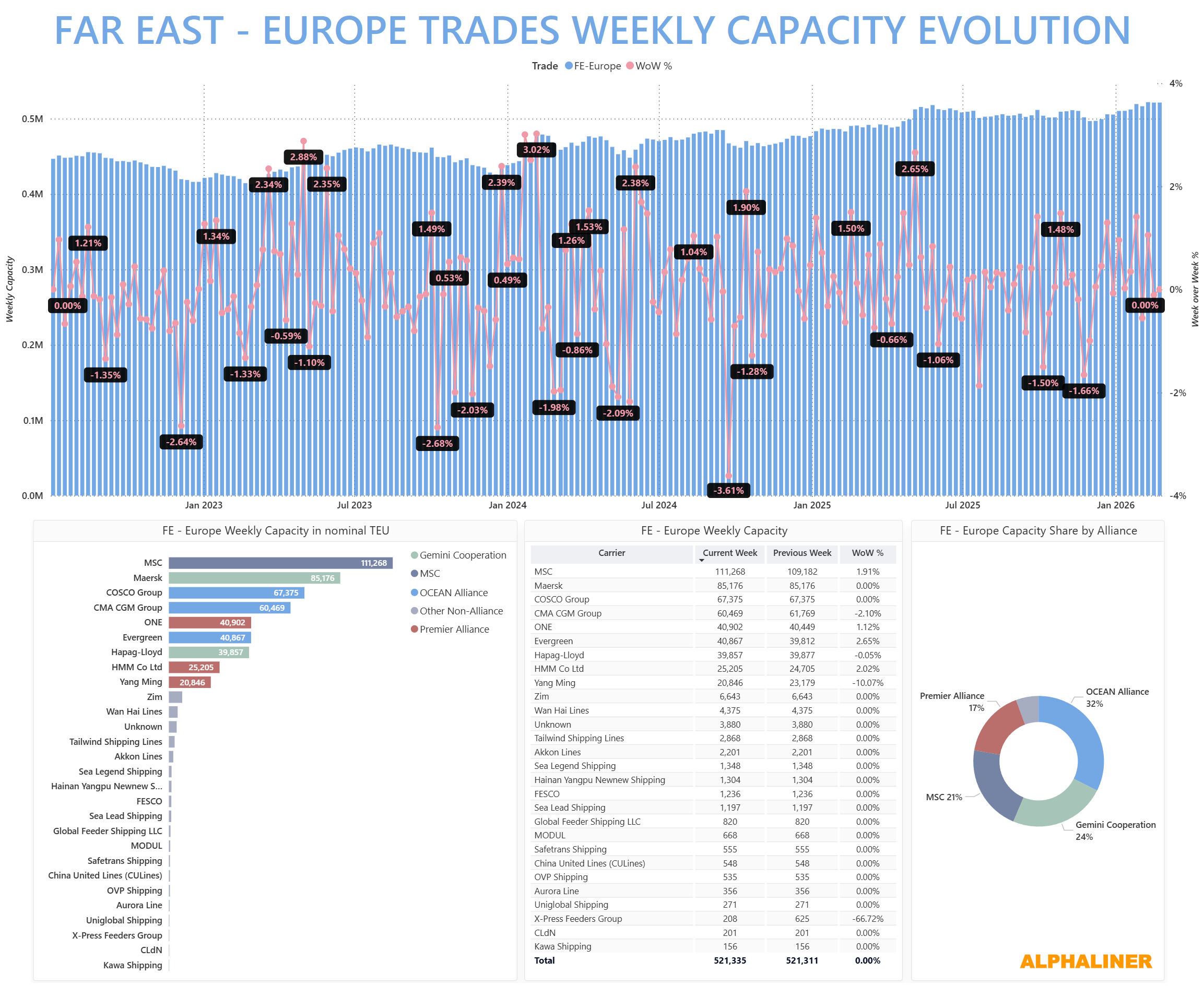

The Asia–Europe maritime route, routed traditionally through the Suez Canal, remains one of the most heavily trafficked lanes in global trade. Despite the Red Sea disruptions, rerouting via the Cape of Good Hope has temporarily increased voyage distances and freight costs.

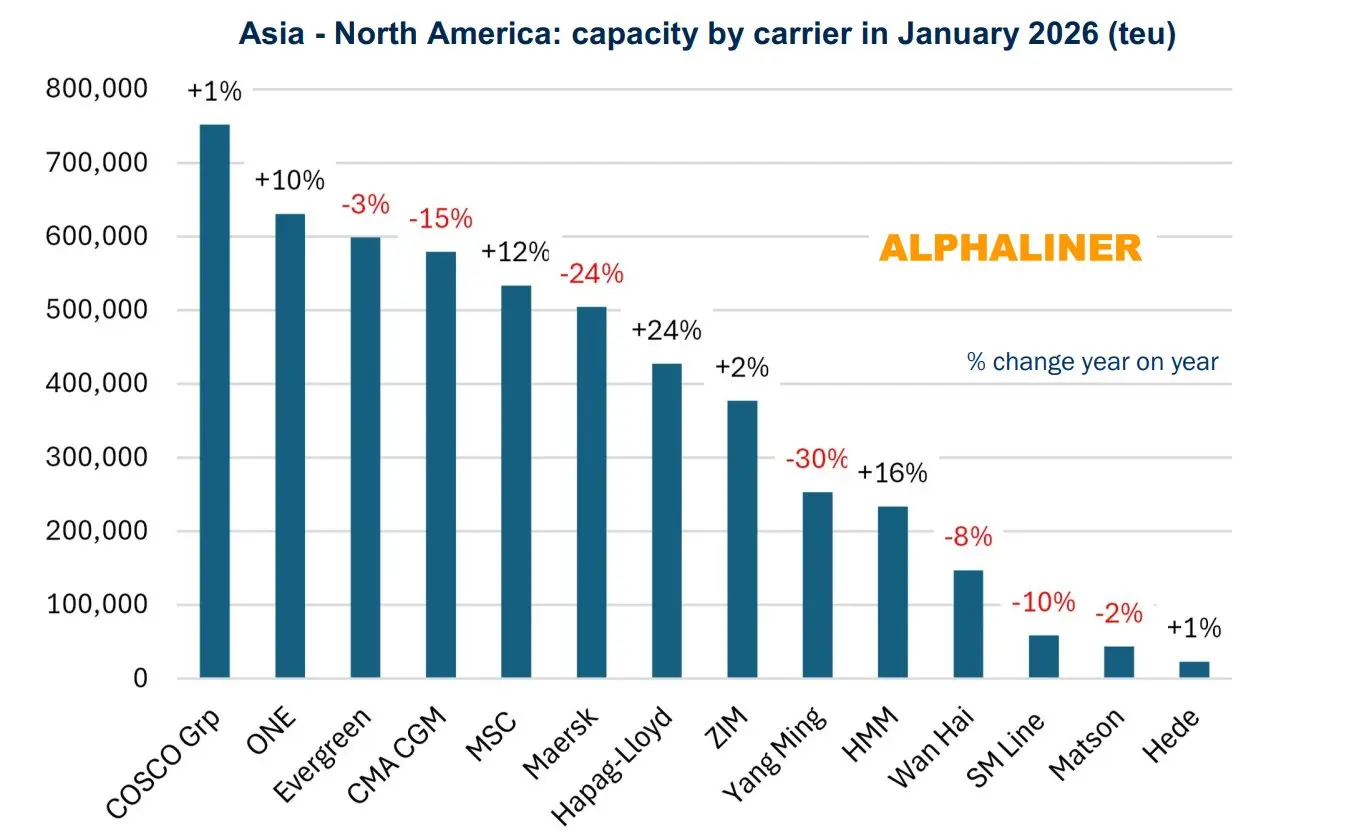

Transpacific and Transatlantic lanes similarly continue to underpin global container flows, but their share of global demand is gradually declining as South–South trade grows and production footprints diversify.

The USMCA corridor stands out as a structural winner. Re-shoring and near-shoring trends are driving higher cross-border flows between the US, Mexico and Canada, establishing the region as a resilient North American manufacturing and logistics powerhouse. This is reinforced by the rise of inland hubs and dedicated cargo airports.

2. New corridors are emerging as strategic alternatives

Geopolitical tension and sanctions have pushed supply chains toward new pathways that bypass traditional bottlenecks.

The Middle Corridor, linking Central Asia to Europe via the Caspian Sea, is becoming a credible alternative to Russia-dependent land routes.

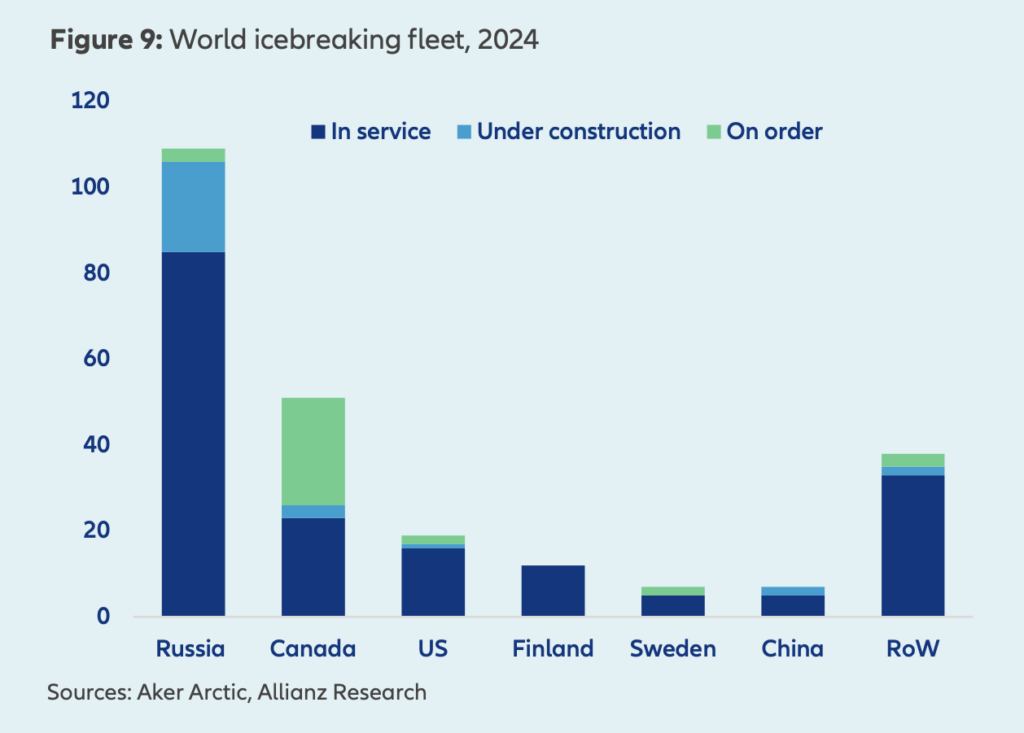

The Northern Corridor is receiving heightened attention due to ice-melt dynamics and competitive icebreaking fleets. Russia remains dominant, but Canada, the US and Finland are expanding capacity.

Africa’s east–west corridors are benefiting from infrastructure upgrades that connect mineral-rich inland regions to coastal gateways.

These newer lanes are not yet close to matching established routes in volume, but they are increasingly important for risk diversification and long-term resilience.

3. Chokepoints remain the greatest sources of risk

Global trade remains highly exposed to a handful of narrow passages:

These chokepoints amplify global price volatility, affecting both shipping markets and supply-chain reliability.

4. The rise of new hubs, airports and logistics nodes

Next-generation trade hubs—spanning Africa, Latin America and South Asia—are becoming more relevant as manufacturing footprints shift. Cargo airports play an increasingly important role in handling high-value goods and stabilising supply chains during maritime disruptions.

5. The Arctic: a long-term wild card

Figure 9 (attached), showing the global icebreaking fleet, highlights how Arctic capability is uneven and geopolitically concentrated. Russia has a dominant fleet advantage, but Canada and the US are strengthening their positions. While regular commercial Arctic shipping remains a long-term possibility rather than an imminent reality, the region’s strategic importance is growing—especially as climate change extends seasonal accessibility.

Source: Allianz Research